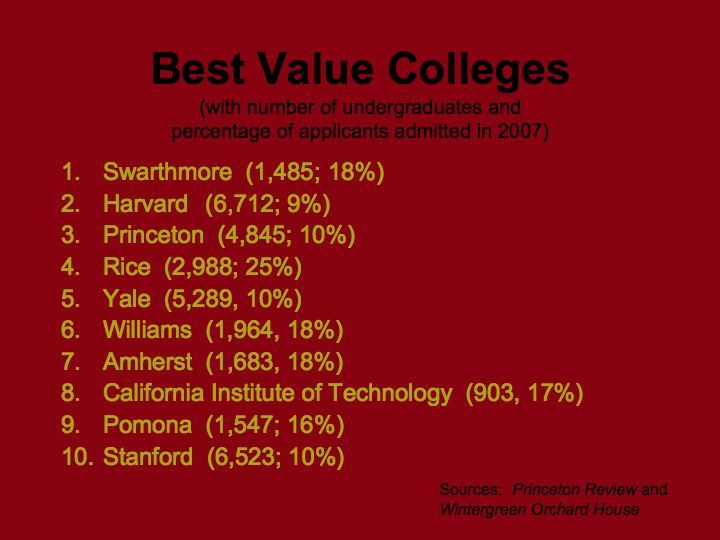

Which colleges can give you the “best bang for your buck”? Check out Princeton Review’s list of “Best Value Colleges” for 2011.

Continue readingMore on the Biggest Party Schools

I recently wrote about Playboy Magazine’s rankings of the top 25 party schools in America.

Today, Inside Higher Ed carries a very thoughtful piece about party school rankings, including those published by the Princeton Review.

The fact is that these rankings are sometimes manipulated by students on campuses. For example, there is some indication that Penn State students pushed one another on various Facebook groups to vote for their school (the rankings are derived from online student surveys).

Are these rankings valid? Probably not, in a statistical sense. And as I have said, nearly every college is a party school in one sense or another.

But the folks at Princeton Review do point out that the schools at the top of the party school list have been fairly consistent over time. (There also is quite a lot of overlap between Playboy‘s list and the Princeton Review‘s list). They also point to the fact that Brigham Young University has been at the top of their “Stone Cold Sober” list for 12 years in a row. So perhaps there is a grain of truth in these rankings.

Mark Montgomery

Educational Consultant

Technorati Tags: party school, party schools, college, university, alcohol, drugs, Playboy, Princeton Review Del.icio.us Tags: party school, party schools, college, university, alcohol, drugs, Playboy, Princeton Review

Value Universities for the "Rest of Us"–A Difficult Claim To Maintain

Today a reader called me out on my decision to focus in a recent post on the Top 10 Value Colleges as identified by the Princeton Review (Kiplinger’s has a similar list, about which I also wrote about).

My reader made the point that public universities can be a better deal, and that the list of public universities on Princeton Review‘s list are much more accessible to the “rest of us” than the ultra-selective “Top 10 Value Colleges” like Harvard and Yale.

Certainly Princeton Review will defend its selection criteria, saying that they have taken into account academic factors as well as financial aid practices. But choosing a college on the basis of this list alone would clearly be silly. In qualitative terms, the education one might receive from William & Mary vs. the New College of Florida would be quite different.

Let’s also look at some interesting facts and figures that are masked by these ratings.

At less than $5,000 a year, tuition at New College is a bargain for residents of Florida. Out-of-staters will be charged over $23,000. Despite the perceived bargain, New College has a transfer rate of 32% (meaning that 32% of freshmen transfer out at some point before graduation), clearly New College is not enough of a bargain to keep a full third of its entering class. Of course, this is likely because New College has a special set of characteristics that might make it more (or less) appealing to some students. Choosing this college only on price would be a mistake.

The College of William and Mary and the University of Virginia accept 34% and 35% of their applicants, respectively. But for applicants from outside the state of Virginia, these schools are as selective as any in the Ivy League. University of California San Diego accepts 46% of its applicants, but is only slightly easier than the two Virginia schools for out-of-state applicants to be admitted. So if you choose three universities based on price, you had better have the goods to be admitted.

CUNY–Hunter College is a large urban university in New York City with a great reputation in many fields, and it accepts 49% of those who apply. Nonetheless, a whopping 64% of its incoming class will not graduate six years later. As one admissions professional I know has said (in another context), to recruit for a school like that is like pouring water into a bucket with a hole in it.

The College of New Jersey qualifies as a hidden gem for many folks, in part because of its small size (about 6,200 undergrads). It accepts slightly less than half of its applicants, and its graduation rate is quite high. However, only 5% of its students hail from beyond New Jersey. As a Colorado boy, I am not convinced many kids I know from the Front Range will stampede to Ewing, NJ, in search of a “bargain”.

This leaves us with one mid-sized university (SUNY Binghamton) with under 12,000 students, and three extra large universities (Florida State, NC State, and Georgia), each with over 30,000 students. These three have impressive graduation rates, are not impossible to get into (yet always more difficult for students from out-of-state). Tuition prices for in-state students run about $16,000, and double that for out-of-staters. But would it really be considered a “bargain” for a student from Colorado to attend SUNY Binghamton and pay more than $40k in tuition instead of attending Colorado State University and paying about $10k? Is SUNY Binghamton that much better, academically speaking, that the Colorado student should consider it a “bargain”?

While I concede to my dear reader that a quality education is available to most students in America–perhaps even at a bargain price–this business of labeling this or that university as a better “value” is not very helpful to the consumer of educational services. As I stated in my previous post, the “bargain” is in the eye of the beholder. The fact that the chartreuse sport coat is very low priced does not mean I will want to buy it (please…I prefer pink). Or how about the those jeans with the 58-inch waist? I see that they are very high quality, but they don’t fit me at all well.

Finding the right college is partly about price. But only partly. Plus, as I have stated elsewhere, the list price of any university is not necessarily the price YOU will pay.

So I’ll say it again. Buy these magazines if you wish to bolster the economy, and I’ll send you my thanks. But if you use these rankings to choose yourself a college, well, caveat emptor.

College Counselor and Personal Shopper

Technorati Tags: college selection, college search, college ratings, college rankings, best value, Princeton Review, Kiplinger’s

Del.icio.us Tags: college selection, college search, college ratings, college rankings, best value, Princeton Review, Kiplinger’s

Best Value Colleges from Princeton Review: Information You Can Lose

The Princeton Review has published its latest list of “best value” colleges. This list sells nice glossy magazines, but provides precious little information to help consumers of higher education (i.e., high school juniors and seniors and their parents) figure out where they will bet the best educational deal.

Case in point: the top 10 “best value colleges” in the United States just happen to be some of the most selective colleges in the country. So this year perhaps 9,000 students (out of about 3 million) will become first year students at the top ten “best value colleges.” What about the rest of America?

More to the point, however, is the fact that Princeton Review’s ostensibly rigorous and objective criteria are based on averages and reported numbers, not on individual cases. While the aggregate numbers are interesting when comparing how different institutions manage themselves (how they construct a budget, how they distribute financial aid, the kinds of students who are most likely to receive grants as opposed to loans, etc.), these aggregate data are NOT helpful to individual students when selecting the college that will provide THAT INDIVIDUAL with the best value.

Buying a college education is not like buying a television set. It is relatively easy for Consumer Reports to test the picture quality, sound fidelity, ease of operation, and the repair histories of inanimate objects like television sets. But an education is highly dependent on the person seeking that education.

To take the television analogy one step further: Consumer Reports can tell you which television rates best on certain criteria. Princeton Review, however, is trying to tell you which channel will be best for you. But a guide cannot tell me which channel is best for me without knowing a whole heck of a lot about me: my preferences, my daily schedule, my ability to pay for premium or cut-rate cable packages, and other variables.

Even when it comes to “value,” a guide like Princeton Review is virtually worthless to the consumer, because colleges reward solid financial aid packages to different kinds of students for different reasons. The financial aid package you receives depends as much upon YOU (your abilities, qualities, interests, commitments) as it does upon the college to which you apply.

So if you want to buy the Princeton Review’s new book, please do so. The economy needs the boost from your spending. But don’t expect to become instantly informed about which college is the best for you. For that sort of information, you need to look elsewhere.

Ratings Skeptic and College Counselor

ADDENDUM: Check out my follow up posts about Kiplinger’s “best value” ratings, and about the “best value universities” as judged by Princeton Review.

Technorati Tags: Princeton Review, Value College, Best College, College Rankings, College Search, College Choice Del.icio.us Tags: Princeton Review, Value College, Best College, College Rankings, College Search, College Choice

Kaplan Test Prep: An Evaluation

I just finished reading Jeremy Miller’s article in the September issue of Harper’s. It’s entitled, “Tyranny of the Test: One Year as a Kaplan coach in the public schools.”

The focus of the article is Kaplan‘s corporate foray into the tutoring business, which has mushroomed since the implementation of No Child Left Behind, which requires school districts to provide tutoring to students who continue to fail to meet expectations. Many private tutoring companies have sprung up to take advantage of this federally mandated program, and the dollars that go with it. The government has increased the amount of money going to the tutoring industry to $2.55 billion.

Miller was a tutor with the program, and describes his experiences in New York’s urban schools. The gist is that the program is not helping students much–especially if you consider the return on investment our government is making.

To me, the problem is that that the tools of NCLB are blunt instruments. Tutors like Jeremy Miller swoop into high schools with the idea of “rescuing” the failing kids by preparing them for exams, such as the Regent’s exam in New York. The fact is, such interventions are mostly futile.

The article is a blistering indictment of NCLB. The act is well-intentioned, to be sure, but the tutoring provision has served only to line the pockets of tutoring companies–and not to significantly raise the achievement of poorer students.

The article also serves as a reminder that the biggest players in the Test Prep industry–who help kids to score well on the ACT and SAT exams–are large companies with a formulaic approach to teaching and learning. Kaplan and Princeton Review have a good track record in the Test Prep business, but their approach is standardized and impersonal.

In recommending test prep services for my clients, I usually try to hook my students up with talented individuals who can tailor their tutoring to the needs of that student. While the testing strategies are the same across the board, each student’s strengths and weaknesses are different.

Individual tutors often cost more, but one should think of the cost as an investment in one’s future. Students usually take these exams only once or twice, and if it’s worthwhile to get some help, its probably worthwhile to get the best help you can get.

Classes like those offered by Kaplan and Princeton Review are not horrendous. But like the tutoring offered in our schools that is described in Jeremy Miller’s article, cannot be fine-tuned to the needs of individual students. If you think it’s ridiculous that we, as a nation, are wasting our money on NCLB tutoring, it’s may be worth considering whether your investment in these test prep juggernauts is worth the price.

Mark Montgomery

Technorati Tags: SAT, Kaplan, Harper’s, ACT, standardized test, tutoring, No Child Left Behind, NCLB, Del.icio.us Tags: SAT, Kaplan, Harper’s, ACT, standardized test, tutoring, No Child Left Behind, NCLB,

Student-to-Faculty Ratios: What Do These Statistics Mean?

The other day I received this question from a client:

Hi, Mark. I’ve been reading college profiles, and nearly all of them cite student-to-faculty ratios, all of which fall in to a relatively narrow range of perhaps 12:1 to 20:1. How important is this statistic in choosing a college?

My short answer: not very

The student-to-faculty ratio is supposed to reflect the intimacy of the educational experience. One would assume that the lower the ratio, the more contact a student will have with faculty members. One might also assume that institutions with lower ratios would have smaller class sizes, on average, than one with a higher ratio.

Let’s look first at the view from 30,000 feet. What is the national student-to-faculty ratio? According to the National Center for Educational Statistics’ Digest of Educational Statistics for 2007. There were 18 million college students and 1.3 million college faculty. A quick calculation tells us that nationwide, there are 13.8 students for every faculty member in America.

However, there are only about 700,000 full-time faculty members in higher education, and about 600,000 part-time faculty, or adjuncts. So if we recalculate the ratio, there are 25.7 students per full-time faculty member.

So how do universities report their student-t0-faculty ratios? Because a low ratio is associated with higher quality education. A college administrator has an incentive to keep this ratio as low as possible.

Every major publication and ranking system (e.g., US News, the Princeton Review, the Fiske Guide) slavishly reports these figures and uses them to compare one college against another.

So look behind the ratios!

- Does this figure include part-time faculty who may be brought in to teach a single course? If so, keep in mind that students have much less access to adjunct faculty (who rarely have their own office or even a place to hang their coats).

- Does this figure include faculty who teach only graduate courses–or may teach predominantly graduate students? If so, the ratio exaggerates students’ access to some of the most senior faculty–many of whom simply do not like teaching undergraduates.

- Does this figure include research faculty, who generally do not teach undergraduate courses at all, but may simply guide doctoral candidates or teach in a graduate professional school? If so, the ratio may be inflated.

When I was a college administrator, my colleagues and I always agonized about how to report our student-to-faculty ratios. The recipient of this information usually colored our responses. If we were reporting to the Office of institutional research (which is required to report information to the federal government in standardized formats). We were fairly careful in giving a more nuanced, detailed accounting.

But if the admissions office was asking for figures. We’d drum up every faculty member we could in order to report a low student-to-faculty ratio. So take these ratios with a grain of salt. As my prospective client noticed, the range of ratios does not vary all that much from one institution to another. And the ratio may not tell you all that much about the classroom experience.

You will want to ask other questions that may tell you more about the intimacy of the educational experience.

For more on whether student-to-faculty ratios tell us much about the quality of a college, click here.

Mark Montgomery

Independent College Counselor